Religious life is one of God’s greatest gifts to his Church, although certain confusions becloud its ‘identity. The Church has attractive definitions of Religious life, especially where it says that it is a consecration to God and a way of perfect charity (LG 44). Lumen Gentium presents the Religious as one of the three fundamental groups that make up the life and mission of the Church. However, it is not an intermediate state between the clerical and lay states; rather, religious life participates in both the hierarchical and lay states (LG 43). Vatican II says, moreover, that although religious life does not belong to the Church’s hierarchical structure, it is a special calling that belongs to the life and holiness of the Church (LG 44).

The Confusion Of Religious Life

Some people think that there is some confusion in this ecclesial definition of the state of religious life in the Church. The documents say that the religion does not belong to the hierarchical state. Yet they do not say that there is a third or intermediate state of life in the Church. Rather, they are very specific in pointing out that religious life is a consecrated state that belongs to the life and holiness of the Church. This means that God calls to the religious life people from both the clerical and lay states. They are called to live the holiness of the Church more intensely in their lives.

Lumen Gentium adds that as a state consecrated to God (LG 45), religious life is the means through which the Church presents Christ to believers and unbelievers alike (LG 46). More beautiful is the definition that describes the religious as those who respond to the call of God to follow Christ more closely through the practice of evangelical counsels and who, through a total lifelong gift of themselves, live more and more for Christ and for his body which is the Church (PC 1). Nothing could be more specific and clearer than these definitions.

The confusion we encounter in religious life is not so much in the definitions as in the living out of the life. In this section, this problem of identity is discussed in relation to my own experiences, in relation to the ignorance of the identity of the religious within the Church, and finally, in relation to the crisis that religious life suffers due to ongoing secularization in the world.

My Religious Life Experiences

The larger part of the twenty-five years I have lived as a nun has been a struggle with the meaning of my life as a religious for me, and the specific place of the religious in the Church. I continued to hope that I was not just being deceived by what I heard people say that religious life is. Partly this work was inspired by the discovery that my struggle for meaning was not personal to me.

Many consecrated people in the Church battle with the same desire to discover who they are and how they are relevant to God and his Church. The way that the Church describes religious life makes so much sense, yet it was difficult for me to identify my lived experiences with the Church’s descriptions. In other words, the meaning of religious life, as defined by the Church, does not in any way reconcile with the lived experience of many religions in the world.

My experience mirrored the problematic relationship in the Church between lived experience and theological interpretations. In other words, a theological definition communicates meaning when it expresses an experience that is shared by the community.

The Hidden Truth

I would like to note that, in all probability, none of the Church’s definitions of religious life was responsible for the initial decision of many religious men and women in Africa to embrace religious life. Most of us had neither any idea of nor any access to the Church’s documents before we came knocking at convent doors. Most of us did not have the opportunity to hear it read to us, and those who had the opportunity probably understood neither the meaning nor the implications.

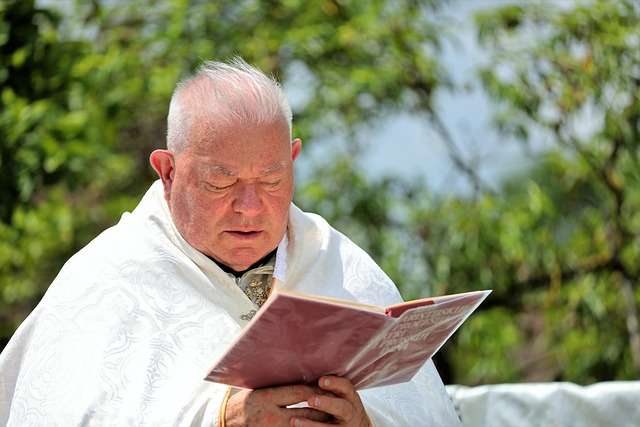

The major attraction to this life came mostly from the person’s initial exposure to spiritual life either by parents or tutors/teachers. It also came from the special ways in which priests and religious present themselves, the spiritual aura they evoke, and the special respect that people accord them.

The day I brought my application to the convent, I was given a form to fill. Apart from certain general questions on family background and initial education, the question in the form was “Why do you want to become a Religious?” I still do not forget my response to that question and how I wrote it. I offered two reasons. I wrote that I wanted to serve God by helping the poor.

My second reason was that I wanted to go to heaven. The sister who interviewed me gave a sweet smile when she read those lines, and after some words of encouragement, she gave me a hug of acceptance and a date to return to the convent. I was seventeen years old and full of zeal for the Lord and heaven. After my return to the convent, it was not long before I discovered that almost all of us, new candidates received that year, gave the same answers to the question.

I wish I knew This Before Now

We grew up thinking that religious life provides the easiest access to God’s heart and heaven. We used to see priests and they appeared very attractive in their Soutanes. The religious women seemed even more attractive, especially in their simple but gorgeous Habits.’ They reminded us of heaven and transcendental realities. We used to see them as those who are ready-made for heaven.

So we opted to join them so that we could spend the rest of our lives in this place where we hoped to gain a thirst for the joys of heaven on earth. Reality soon dawned on us because we had hardly spent three months of postulancy then we saw that within the convent walls much work still needed to be done for the journey that leads to God. “Why did we leave home after all” was the persisting question, since reality did not match expectations.

My experiences made me aware of the fact that many married people serve. God is better than the supposed religious. I realized that at least my mother seemed to me to be closer to God than most people (encountered within the walls of the convent. 1 cite any mother as representative of most parents and lay people who live heroic lives of witness to Christ within the family and social setting. Yet the lectures I received during those formative years emphasized the superior quality of the religious life and how it makes sense.

Conflicting experiences

It seemed to me that there were very few experiences on the ground, very little indeed to give sufficient corroboration to the definitions that were given. Conflicting experiences motivated different decisions in us. One might be discouraged from continuing based on a terrible encounter, and before the mind is fully made up, a positively different encounter reverses the decision previously taken. The convent is a place where one is constrained to see reality with the eyes of a biblical sage.

There, reality is not either good or bad. It is a place where one finds people who are good and bad, wise and foolish, just and unjust, pious and wicked, beautiful and ugly, tall and short, fat and thin. The list includes and exhausts all contradicting categorizations.

The convent is a factory where saints are made. Like every factory, raw materials are sent there, materials that are crude, coarse, unprocessed, unrefined, and untreated. Like every factory, it has many departments, each responsible for the production stage of the product. Saints are not made in heaven; they are made here on earth, but they are acknowledged and glorified in heaven. It would be an illusion to hope to find only saints there.

What is the job of Seminary And Convent

Like every factory, the convent and the seminary house people who represent factory appliances and devices for the mauling, processing, and refinement of those who would become saints. Some are gradually becoming saints. Others are there to prepare them for sainthood. One must fit into one of the categories. This is why the convent harbors humanity in its strength, purity, nakedness, goodness, ugliness, and wickedness. What we could not fathom was what makes this factory unique.

When does the material become a finished product? The truth is that the entire production stage does not all take place in the formation houses. It lasts as long as the life span of the person in question.

The novice is frightened, disoriented, and discouraged at the initial encounter with the orchestration of human negative realities in customary holy places. Within the convent walls, the novice expects God revealed in loving, kind, forgiving, generous, and compassionate persons. One expects to find people who are capable of conversion and reciprocal support.

At least, the number of such people should enjoy an absolute majority in the opinion poll. For us then, anything less of these expectations was dysfunctional. As we struggled to make sense of the disconnection between ideas and lived reality, we seemed like those who were being led through specious paths but we continued to journey like Abraham as went his way to sacrifice Isaac.